|

|

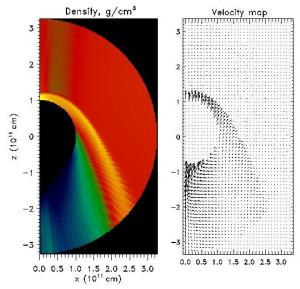

Figure 1: 2D Hydrodynamical

simulations of a star passing through an

inactive cold disk. The star is modeled as a rigid

sphere centered at x,z = 0,0

with radius of 1011 cm. The left image shows the

gas density, with red representing unshocked disk material, and yellow the

shocked gas. The star is moving along the z-axis in the upward direction,

drilling a narrow hole in the disk. Velocity vectors are shown on the right.

|

|

|

|

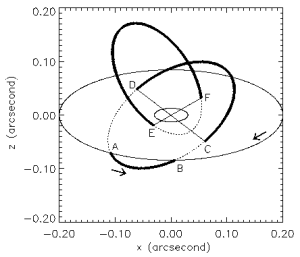

Figure 2: Examples of star's

orbits and the expected flares and eclipses.

The star moving on the ABCD track hits the disk in

points C and D where intense X-ray and weaker near infra-red flares will

be emitted. The coordinates of four such points (e.g. CD and EF) will

define the plane of the disk rotation. Eclipses in points A and B will

constrain the disk size. (From Nayakshin

& Sunyaev 2003).

|

|

|  |

The center of our Galaxy hosts a super massive black hole

that is about 3 million times more massive than our Sun ( Schoedel

et al. 2002; see also T.

Ensslin highlight contribution).

A decade long mystery is why the black hole radiates

only about 0.0001 of the luminosity that is expected from the accretion

of hot gas that is observed to be around it. MPA researchers suggest that

there exists a cold inactive disk around the black hole, a remnant

of past vigorous accretion.

While the disk is too cold (about a 100 K) to be directly

visible, it is much more massive than the hot gas seen in X-rays. According to the new research, when the

hot gas comes into physical contact with the cold disk, the heat is rapidly drained from the hot gas via

thermal conduction. The hot flow effectively gets frozen, and settles

onto the inactive disk at large distances from the black hole. Since the

hot gas is prevented from falling into the black hole's potential well, little

X-ray radiation is emitted (Nayakshin

2003.

The second mystery of our Galactic Center are bursts of

X-ray radiation that happen roughly once per day

and can be more than 100 times brighter than the black

hole quiescent emission. These X-ray flares were discovered two years ago (Baganoff

et al. 2001 ) and are so unique that no reasonable explanation

was givenup to now. However the inactive disk hypothesis

made by the MPA researchers offers a very natural and

easily testable model for the flares. The point is that

there are thousands of stars in the innermost part of our

Galaxy (see

the movie on the MPE infrared group's home page). These

stars rotate with extraordinary high velocities around the super massive

black hole. Generally speaking, these stars will hit the inactive disk

twice per orbit.

While passing through the disk, the stars create a shock

wave which emits X-ray radiation (Fig. 1). The properties of flares expected

from such events are very similar to that actually observed (Nayakshin

& Sunyaev 2003). In addition, the model shows that

similar star-disk encounters yield flares that are too weak to observe in more distant Galactic centers, explaining why these

X-ray flares have been observed only from our

Galactic Center.

The MPA researchers further suggest that observations

of such flares and expected eclipses (see Fig. 2) in the

future will allow us to determine the inactive disk properties

(i.e. mass, size, plane and direction of rotation).

This information should yield crucial clues on the history

of black hole formation in our Galaxy. In addition,

since our Galactic Center is presumed to be similar to

that of many other inactive Galaxies, the discovery of

the inactive disk in our Galaxy could signal a change

in the paradigm of the accretion processes in all the inactive Galaxies.

Sergei Nayakshin

|