|

|

Figure 1: The core of the Seyfert 2 galaxy NGC 7742. The lumpy thick ring

around the core is an area of active star formation. The ring is about

3000 light-years from the core.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2: A torus of dusty material is thought to surround the accreting

black holes in most AGN. For type 2 AGN, the observer's view of the

light from the central source is blocked by this material. Radiation

which escapes perpendicular to the torus is able to ionize gas

clouds in the surrounding galaxy, which leads to characteristic

emisson line signatures in the galaxy spectrum.

|

|

|

|

|

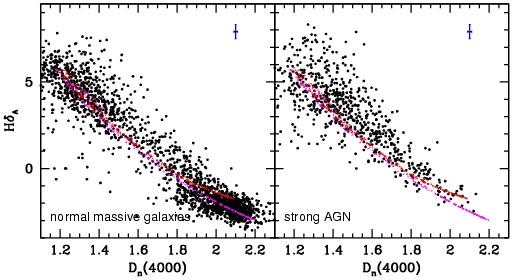

Figure 3: A starburst "diagnostic" diagram for AGN in the Sloan

Digital Sky Survey. The magenta and red points show the predicted

location of galaxies that have had continuous star formation histories.

Most normal galaxies (left) lie close to these predictions.

A significant fraction of powerful AGN (right) are displaced

away from the locus occupied by the continuous models. This shows that they

must have experienced recent starbursts.

|

|

|  |

Active galaxies are also noteworthy in that they display very strong cosmological

evolution. The most luminous active galaxies were a thousand times more numerous

at redshift 2.5 than they are today. This strong evolution with redshift

suggests that galaxy formation and the creation of active nuclei may have gone

hand-in-hand in the early Universe.

Although they are numerous, it is not possible to study distant AGN in detail,

because the light from the surrounding host galaxy is usually too faint to detect.

In order to understand the physical processes that are responsible for

fuelling the central black holes in galaxies, it is more useful

to study AGN in the local Universe.

In collaboration with a group at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore

(T. Heckman, C. Tremonti and S. Ridgway), scientists at MPA are

studying a very large sample of 22,000 AGN drawn from the Sloan

Digital Sky Survey. The active galaxies under investigation are

so-called Type 2 AGN. In these objects, most of the radiation emitted

by matter very close to the black hole is obscured by a central dusty

"torus". Radiation can, however, escape at right angles to the plane

of the torus (see Fig. 2) and ionize gas further out in the

galaxy. This causes characteristic emission lines to appear in the

spectrum of the galaxy, which diagnose the presence of the active

nucleus. Most of the luminosity that is produced as material falls

onto the black hole is thus hidden from view in Type 2 AGN. As a

result, it is possible to obtain a much clearer picture of the

surrounding host galaxy. It is then possible to ask how galaxies that

contain actively accreting black holes differ from galaxies in which

the black hole lies dormant.

The main conclusion reached by the MPA/JHU team is that strong AGN activity is often

associated with strong bursts of recent star formation in the host galaxy

(see Fig. 3). Conversely, in bulge-dominated

galaxies where black holes lie dormant, star formation has almost

always stopped. This so-called starburst-AGN connection has been a

controversial subject among AGN specialists for many years. The results of the

MPA/JHU group establish that AGN activity and star formation are inextricably linked

in massive, bulge-dominated systems.

Astronomers interested in galaxy formation must now turn their attention

to undertanding how the formation and fuelling of central supermassive black holes

influenced the evolution of their galactic hosts.

Guinevere Kauffmann

|