|

|  |

Stars with more than roughly eight times the mass of our sun end their lives

in gigantic explosions, so-called supernovae. These spectacular events belong

to the most energetic and brightest phenomena in the universe and can outshine

a whole galaxy for weeks. Supernovae are not only the cosmic sources of chemical

elements like carbon, oxygen, and silicon, which are fused over millions of years

of quiescent stellar evolution and disseminated into circumstellar space by the

blast wave. Supernovae are also important producers of iron and heavier

trans-iron elements, which can be freshly assembled during the explosion.

While supernovae eject most of the material of the dying star, the stellar core

of iron collapses under the influence of its own gravity within fractions of a

second to an extraordinarily exotic, ultra-compact remnant, a neutron star. Such

an object contains about 1.5 times the mass of our Sun, compressed into a sphere

with the diameter of Munich. The central density of a neutron star exceeds

that in atomic nuclei, gigantic 300 million tons (the weight of a mountain)

in the volume of a sugar cube.

The matter in newly born neutron stars is extremely hot, up to

temperatures of more than 500 billion degrees. At such conditions

particle reactions involving neutrons, protons, electrons and positrons

(the anti-particles of electrons) create huge numbers of neutrinos.

Cooling neutron stars thus radiate a total of 1058 of these

uncharged, nearly massless elementary particles, which interact extremely

rarely with matter on earth. Only one of a billion neutrinos coming from a

supernova (or from the sun, which also produces neutrinos in the nuclear fusion

"reactor" that burns at its center) hits a particle somewhere inside

the earth, all the others cross through the whole of the earth's body

without a single collision.

Neutron stars release neutrinos and their anti-particles in three different

flavors, corresponding to the three known families of charged leptons:

electron neutrinos, muon neutrinos and tau neutrinos. These neutrinos are

expected to be radiated equally in all directions, because neutron stars

are nearly perfectly spherical objects due to their extremely strong

gravitational fields. Most previous computer models of neutron star

formation therefore assumed spherical symmetry.

Only recently the first three-dimensional simulations with a detailed

treatment of the complex neutrino physics have become possible due to the

increased power of modern supercomputers (see  here ). here ).

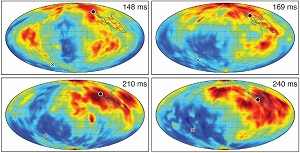

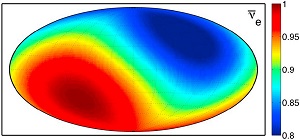

As expected, the neutrino emission starts out to be basically spherical except

for smaller variations over the surface (see Fig. 1, upper left panel). These

variations correspond to higher and lower temperatures associated

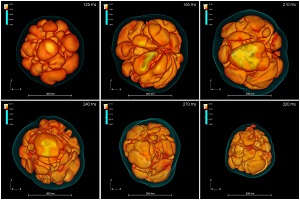

with violent "boiling" of hot matter inside and around the newly

formed neutron star, by which bubbles of hot matter rise outward and

flows of cooler material move inward (Fig. 2). After a short while and

gradually growing, however, the neutrino emission develops clear

differences in two hemispheres. The

initially small patches merge to larger areas of warmer and cooler medium

until the two hemispheres begin to radiate neutrinos unequally. A stable

dipolar pattern is established, which means that on one side

more neutrinos leave the neutron star than on the other side.

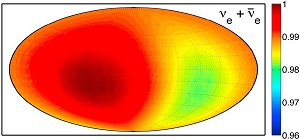

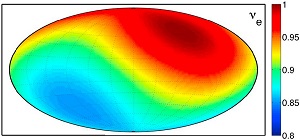

Observers in different directions will thus receive different neutrino

signals. While the directional variation of the summed emission of all kinds

of neutrinos is only some per cent (Fig. 3 top), the individual neutrino

types (for example electron neutrinos or electron antineutrinos) show

considerable contrast between the two hemispheres with up to about

20 per cent deviations from the average (Figs. 3 middle, 3 bottom). The directional

variations are particularly pronounced in the difference between

electron neutrino and antineutrino fluxes (Fig. 1, lower right panel),

the so-called lepton number emission.

The possibility of such a global anisotropy in the neutrino emission was

not predicted and its finding in the first-ever detailed three-dimensional

simulations of dynamical neutron-star formation comes completely unexpectedly.

The phenomenon exhibits astonishing properties: In spite of ongoing violent

bubbling motions of the "boiling" hot and cooler gas, which lead to

rapidly changing structures in the flow around and inside the neutron

star (Fig. 2), the dipolar neutrino emission asymmetry establishes itself

in a stable state. It thus exists for long periods of time, during which

only a slow and moderate drift of its orientation can be observed (cf.

the thin, dark-grey line in Fig. 1).

The team of astrophysicists named this new phenomenon "LESA" for

Lepton-Emission Self-sustained Asymmetry, because the emission dipole seems

to stabilize and maintain itself through complicated feedback effects:

Interactions with the asymmetric neutrino flow affect the collapse of

the stellar core such that a hemispheric asymmetry develops in the

matter falling inward to the nascent neutron star. This accretion

asymmetry then continues to feed additional anisotropic emission of

neutrinos. These findings suggest that the spherical collapse of a

stellar core to a neutron star is not stable but the system wants to

rearrange itself into a dipolar asymmetry mode.

If LESA happens in collapsing stellar cores, it will have important

consequences for observable phenomena connected to supernova explosions.

Neutrinos radiated from the nascent neutron star interact with the

innermost material that gets ejected by the supernova blast wave. In doing

so, neutrinos determine the ratio of neutrons to protons in the expelled

plasma, which is a crucial requisite for the subsequent formation of

heavy elements when the outflow cools. A directional variation between

electron neutrino and antineutrino emission will thus lead to differences

of the chemical element production in different directions.

Moreover, a global dipolar

anisotropy of the neutrino emission carries away momentum and thus imparts

a kick to the nascent neutron star in the opposite direction. Because of

the huge number of escaping neutrinos, an emission asymmetry

of only one per cent, if lasting for several seconds,

could account for a neutron-star recoil of 100 kilometers per second.

Also the neutrino signal arriving at Earth from the next supernova event

in our Milky Way must be expected to depend on the angle from which we

observe the supernova. Detailed predictions of measurements with big

underground facilities like the IceCube detector at the South Pole and the

SuperKamiokande experiment in Japan therefore need to take into account

the directional variations found in the new three-dimensional models.

However, the stunning neutrino-hydrodynamical instability

that manifests itself in the LESA phenomenon is not yet well understood.

Much more research is needed to ensure that it is not an artefact

produced by the highly complex numerical simulations. If it is physical

reality, this novel effect would be a discovery truly based on the use of

modern supercomputing possibilities and not anticipated by previous

theoretical considerations.

Hans-Thomas Janka

References:

Self-sustained asymmetry of lepton-number emission: A new phenomenon during the supernova shock-accretion phase in three dimensions;

Tamborra I., Hanke F., Janka H.-Th., Müller B., Raffelt G.G., Marek, A.;

Astrophys. Journal 792, 96 (2014),

http://arxiv.org/abs/1402.5418 http://arxiv.org/abs/1402.5418

Neutrino signature of supernova hydrodynamical instabilities in three dimensions;

Tamborra I., Hanke F., Müller B., Janka H.-Th., Raffelt G.;

Physical Review Letters 111, 121104 (2013),

http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.7936 http://arxiv.org/abs/1307.7936

Neutrino emission characteristics and detection opportunities based on three-dimensional supernova simulations;

Tamborra I., Raffelt G., Hanke F., Janka H.-Th., Müller B.;

Physical Review D 90, 045032 (2014),

http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.0006 http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.0006

|