|

|

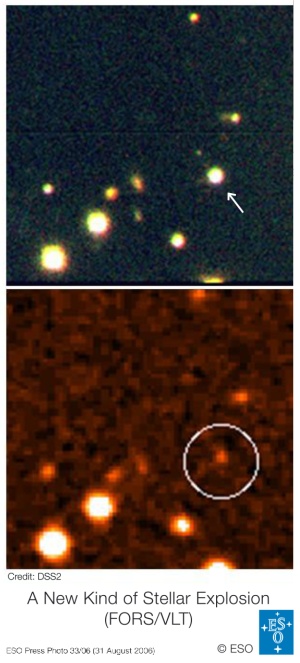

The lower panel shows an image of the sky prior to the explosion of

Supernova SN 2006aj. The source inside the circle is the faint host

galaxy of the supernova at a distance of 430 million light years from

Earth. The upper panel is the image of SN 2006aj (arrow) taken with the

Very Large Telescope of the European Southern Observatory.

Both images are about 1 arcminute across.

|

|  |

Stars shine because nuclear reactions take place in their cores, converting

lighter elements into heavier ones and liberating energy in this process. When

a massive star exhausts its nuclear fuel, gravitational forces cause the core

of the star to collapse. This triggers the explosion of the star. Part of the

stellar material is ejected at very high velocities and the rest forms a

compact central remnant, a neutron star or, for sufficiently massive exploding

stars, a black hole. Nuclear burning and heating by an outgoing shock wave at

the time of the explosion produce a very bright light display, which for a

few days makes the exploding star as bright as an entire galaxy. Such events

are called supernovae.

A particular group of extremely energetic supernovae produce gamma-ray bursts.

These are extraordinarily bright flashes of gamma- and X-ray radiation, which

last typically 10--100 seconds and come from distant galaxies. Previous

observations have shown that supernovae connected with long-duration gamma-ray

bursts result from the collapse of stars with more than about 40 solar masses,

which have stripped their outer hydrogen and helium envelopes during their

preceding evolution. Such a massive progenitor is likely to collapse to a

black hole. The formation of a black hole at the center of a star was

thought to be a requirement for the launch of a gamma-ray burst.

Gamma-ray bursts have a weaker equivalent called X-ray flashes. These events

are less bright than gamma-ray bursts and have fewer gamma-ray photons, but are

otherwise similar to gamma-ray bursts. "There had been suggestions that

X-ray flashes may also be linked to core-collapse supernovae, but they are

fainter and therefore harder to locate, and so they have not been studied as

much as gamma-ray bursts", says Elena Pian of the Italian National Institute for

Astrophysics.

On Feb. 18, 2006, the NASA Gamma-Ray Burst Satellite Swift detected an X-ray

flash, XRF 060218, at a distance of 140 Megaparsecs. This is sufficiently

nearby that researchers could try to find an associated supernova using the

8-metre Very Large Telescopes of the European Southern Observatory in Chile.

This effort was indeed successful, and spectra taken a few days after the burst revealed

clear supernova characteristics. This supernova, SN 2006aj, became almost as

bright as the supernovae associated with gamma-ray bursts, and it had similar

spectra.

Scientists at the Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching modelled

the spectra and light curve of SN2006aj to determine its intrinsic properties.

"We found that both the explosion energy and the mass ejected in SN 2006aj were

intermediate between the supernovae that are associated with gamma-ray bursts

and those that are not", says Paolo Mazzali of the Max-Planck Institute for

Astrophysics. This is in line with the weakness of the X-ray flash

compared to a gamma-ray burst. "It suggests that the supernova was produced by

a star whose initial mass was only about 20 solar masses. A star of that mass

is expected to form a neutron star rather than a black hole when its core

collapses", explains Mazzali.

"Since less massive stars are much more numerous than more massive ones, this

type of event may indeed be very common. But its relative dimness makes it

harder to observe", adds Elena Pian.

These new results indicate that the connection between supernovae and gamma-ray

bursts extends to a broader range of stellar masses than previously thought.

It is possible that such explosions involve different physical mechanisms.

"While more massive stars probably collapse to a spinning black hole,

it could be magnetic activity of a rapidly rotating nascent neutron star,

which launches an X-ray flash in case of less massive stars", speculates Mazzali.

More good observations are needed to understand the true reason for the new

findings. Currently it is not clear what distinguishes the stars that

explode and produce an X-ray flash from those that end their lives as ordinary

supernovae.

Original publication:

Paolo Mazzali, Jinsong Deng, Ken'ichi Nomoto, Daniel N. Sauer,

Elena Pian, Nozomu Tominaga, Masomi Tanaka, Keiichi Maeda, &

Alexei V. Filippenko:

A neutron-star-driven X-ray flash associated with supernova SN 2006aj,

Nature, Vol. 442, Band 7106 (31. August 2006)

Contact for more information:

Dr. Paolo Mazzali

Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics

Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1

D-85741 Garching

Tel.: +49 89 30000-2221

Fax: +49 89 30000-2235

E-mail: mazzali@mpa-garching.mpg.de

|