|

|  |

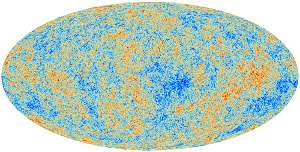

The all-sky map released now is based on the first 15.5 months of

observations with the Planck space telescope, a mission of the

European Space Agency (ESA), and shows the oldest light in the

universe. This was emitted when the universe was only 380,000 years

old and became transparent for the first time after the Big Bang. The

"primordial soup" of protons, electrons and photons cooled gradually,

allowing neutral hydrogen atoms to form and the light to escape. As

the universe continued to expand and to cool, this radiation was

shifted to longer wavelengths, so that it is received today as the

cosmic microwave background (CMB) at a temperature of about 2.7

Kelvin.

Tiny temperature fluctuations in this CMB map reflect smallest density

fluctuations in the early universe. "The Planck CMB map provides us

with an extremely detailed picture of the very early universe," said

Simon White, Co-Investigator in the Planck Collaboration and director

at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics (MPA), who helped to

establish the standard model of cosmology in the 1980s by analysing

the evolution of structure in the universe. “All the structures that

we see today grew from tiny density fluctuations shortly after the Big

Bang.”

Planck was designed to measure these fluctuations across the whole sky

with greater resolution and sensitivity than ever before, allowing

scientists to determine the composition and evolution of the universe

from its birth to the present day.

"The Planck data fit extremely well with the standard model of

cosmology," says Torsten Ensslin, who is managing Germany's

participation in the Planck mission at MPA. "The cosmological parameters have

been refined with Planck more accurately than ever, and our analysis

passed all tests against various other astronomical observations with

flying colours."

The analysis of the Planck data show that normal matter, making up

galaxies, stars and also Earth, contribute only about 4.9% to the mass

and energy density of the universe. About 26.8% is dark matter, which

interacts only through its gravitational effect – contributing far

more than previously assumed. Dark energy, the mysterious component

that causes the universe to expand ever faster, on the other hand,

accounts for only 68.3%, less than expected. Finally, the Planck data

also set a new value for the rate at which the Universe is expanding

today, known as the Hubble constant. At 67.15 km/s/Mpc, this is

significantly less than the current standard value in astronomy. The

data imply that the age of the Universe is 13.82 billion years.

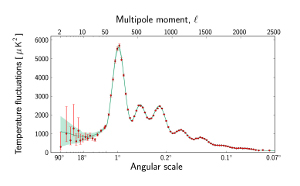

However, because the precision of Planck’s map is so high, it also

revealed some peculiar unexplained features, which cannot easily be

reconciled with the standard model. One of the most surprising

findings is that the fluctuations in the CMB temperatures at large

angular scales are not as strong as expected from the smaller scale

structure revealed by Planck. Another is an asymmetry in the average

temperatures on opposite hemispheres of the sky. This runs counter to

the prediction made by the standard model that the Universe should be

broadly similar in any direction we look. Furthermore, a cold spot

extends over a patch of sky that is much larger than expected. This

data could point to an extension of the standard model or even new

theories.

“But even if we do not yet understand these anomalies, we can

eliminate the possibility that they are due to foreground effects,”

says Torsten Ensslin. “The ‘cold spot’, in particular, has been known

for quite a while and could well be a statistical fluctuation.”

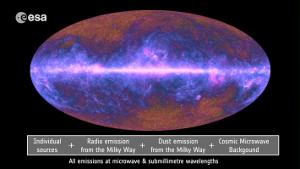

The MPA scientists have been involved in software development even

from before the beginning of the mission, to process the data and

remove foreground emission from objects such as galaxies, quasars, and

even our own Milky Way. By now, their work focuses on analysing

information from the cosmic microwave background radiation and trying

to better understand our universe.

One aspect, amongst many others, is the discovery and measurement of

galaxy clusters by the Sunyaev-Zel'dovich effect. The SZ effect is a

characteristic signature imprinted by galaxy clusters on the cosmic

microwave background, when the light from the CMB passes through the

cluster. Because of the different frequency bands available with

Planck, the SZ effect can be used as a unique tool for detecting

galaxy clusters.

Rashid Sunyaev, Co-Investigator in the Planck Collaboration and

director at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, together with

Yakov Zel'dovich predicted not only the effect of galaxy clusters on

the CMB but also the existence of the acoustic peaks in the CMB itself

which Planck has now measured so precisely. He is excited by the

Planck results: "When we developed our models of the CMB radiation

more than 40 years ago, we thought of it mainly as a theoretical

thought experiment. It is amazing that the measurements are now so

detailed that it can even be used as tool to discover hundreds of new

galaxy clusters that where unknown before. A great success for

Planck!”

Planck scientists were even able to use this sample of clusters of

galaxies to derive key parameters of the universe – a method that has

been employed with CMB data for the first time. This is an additional

and completely independent method from the way which uses the shape and

amplitude of the acoustic peaks.

For more information:

The new data from Planck are based on the first 15.5 months of its all-

sky surveys, about half of the data expected from the mission overall.

Launched in 2009, Planck was designed to map the sky in nine

frequencies using two state-of-the-art instruments: the Low Frequency

Instrument (LFI), which includes the frequency bands 30–70 GHz, and

the High Frequency Instrument (HFI), which includes the frequency bands

100–857 GHz. HFI completed its survey in January 2012, while LFI

continues to operate.

Planck’s first all-sky image was released in 2010 and the first

scientific data were released in 2011. Since then, scientists have

been extracting the foreground emissions that lie between us and the

Universe’s first light to reveal the CMB presented in this release.

The next set of cosmology data will be released in early 2014.

The Planck Scientific Collaboration consists of all the scientists who

have contributed to the development of the Planck mission, and who

participate in the scientific exploitation of the Planck data during

the proprietary period. These scientists are members of one or more of

four consortia: the LFI Consortium, the HFI Consortium, the DK-Planck

Consortium, and ESA's Planck Science Office. The two European-led

Planck Data Processing Centres are located in Paris, France and

Trieste, Italy.

German participation in the Planck mission is based at the Max Planck

Institute for Astrophysics (MPA), as Rashid Sunyaev and Simon White

are the German co-Investigators in the two instrument consortia. It is

funded by the German national aeronautics and space research centre

DLR and the Max Planck Society (MPG). MPA and MPG support the

scientific participation in the mission, DLR the majority of the

technical contribution, especially the MPA Planck Analysis Centre

(MPAC).

The MPAC is responsible for providing data analysis infrastructure for

data centres and for the individual Planck scientists. Within the IDIS

data system of Planck (Integrated Data and Information System), the

MPAC is responsible for both the provision of a workflow engine and a

data management component and also has to provide development,

integration and operation of the data simulation pipeline.

Link:

An explanation of the cosmic microwave background radiation can be found

in a comic, which was created in 2009:

Riding early waves Riding early waves

Contact:

Dr. Torsten Enßlin

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik

Tel. 089 30000-2243

E-mail: tensslin mpa-garching.mpg.de mpa-garching.mpg.de

Dr. Hannelore Hämmerle

Pressesprecherin

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik

und Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik

Tel. 089 30000-3980

E-mail: pr mpa-garching.mpg.de mpa-garching.mpg.de

|

mpa-garching.mpg.de

mpa-garching.mpg.de