14 billion years of cosmic history in one:

|

|

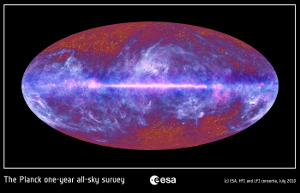

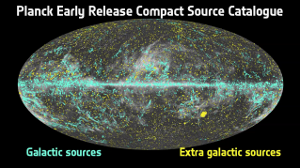

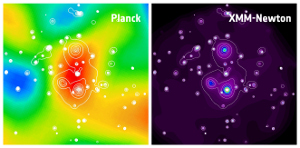

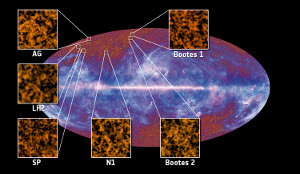

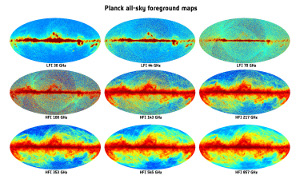

Already the start of the mission was very promising: Following 10 years of preparation, the Planck collaboration, which includes a team at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, observed a launch right out of the textbook on 14th May 2009. As the satellite reached its operating position some 1.5 million kilometres outside the Earth’s atmosphere in summer 2009, right on schedule the sensitive instruments had been cooled to their working temperature of in some cases only 0.1 degrees above absolute zero. This means that they are able not only to observe the 2.7 Kelvin emission of the very early universe, right after the Big Bang, but also to produce precise maps of its tiny temperature variations of just a few millionths of a degree. These temperature variations are the first indicators of all observable structure in the universe, stars, galaxies and galaxy clusters. Even though Planck can only look back to a time about 380 000 years after the Big Bang, from its data the scientists glean insights into the first few fractions of a second, when the cosmic structures were seeded, some 14 billion years ago. Planck’s primary aim is the measurement of these temperature fluctuations with unprecedented accuracy. For this, Planck scans the sky in nine frequencies, ranging from high-frequency radio waves at 30 gigahertz (GHz) to the far infrared with 857 GHz. The scientists need this broad frequency range as Planck observes not only the primordial emission but also noise from galaxies. This interfering signal, however, has a different spectral distribution, which can be identified, measured and subtracted due to the multi-frequency measurements with Planck. And while this foreground signal is an annoyance to cosmologists who want to look back to the cosmic nursery, as by-product it provides valuable information to galaxy researchers. The largest part of this foreground light comes from our own galaxy, the Milky Way. As we are inside the galactic disk, we see the interstellar medium all around us, either due to the thermal radiation of dust clouds at high frequencies or due to the radio emission of electrons moving nearly with the speed of light in the galactic magnetic field. So far, Planck has produced three complete scans of the whole sky, thus fulfilling its primary objective. However, as it continues to function perfectly, it will probably stay in operation until the start of 2012 and continue to provide data. The results gained from the first year of Planck data were first presented on 11th January 2011, where many of these results are based on the ”Early Release Compact Source Catalogue“ with some 15 000 compact sources. The early release of this data enables scientists to arrange for detailed follow-up observations with other telescopes such as the Herschel space telescope with operates at similar wavelengths. At the same time as the catalogue, 25 scientific papers are published with topics covering many orders of magnitude and objects and ranging from studies of individual objects in the catalogue and analyses of galactic emission to the first cosmological results on galaxy clusters and the light of early galaxies. Highlights of these papers include:

The results presented at this Planck conference mainly cover the astrophysical by-products of the Planck mission. The data related to Planck’s primary goal, the cosmic microwave background, the resulting conclusions regarding the age, structure and composition of the universe as well as insights into its origins will probably be published in 2013. Until then, the noise signal from space but also from the instruments has to be understood in more detail. The team at the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics will contribute to this effort — their software for simulating and processing the data will continue to be in daily use. At the same time, the institute, in particular the Planck co-investigators Simon White and Rashid Sunyaev, who predicted the Suyaev-Zeldovich effect in 1969, as well as Torsten Enßlin, the head of the German contribution to Planck, and their groups, will help to increase the scientific gain of the mission. Contact:

Local contact: |

mpa-garching.mpg.de

mpa-garching.mpg.de